But only humans can create and sustain community…

As one who writes as part of my clergy profession and other pursuits, I am often tempted by those automated pop-up prompts asking if I wish utilize A.I. I typically decline— but not always. I suppose I just can’t shake the ingrained ethic about doing my own work, and that doubtless comes from years of formal education. I learned to cite sources and to footnote in high school, a skill that was enhanced in college and then honed in law school and seminary.

I do have a doctoral dissertation that bears my name, and I am still meticulous about avoiding plagiarism— a commitment that goes back to my sophomore year at Wayne State University and a helpful conversation with a teaching assistant in an economics course.

But that’s just me.

So, on those occasions where I might employ an A.I. summary, for example, it is always after having considered the accuracy of the words being offered to me. There have been instances where A.I. makes up facts and “fudges” figures, as author Stephen Witt reports. There is often a built-in bias, Witt says, to give a business executive answers that likely result in the most profitable course of action without regard to objective truth.

The business applications of A.I. are one thing, but human monitoring becomes critical where health care issues are concerned, and that is just one example. I mean, what could possibly go wrong when A.I. disapproves a particular medical procedure? Health insurers are increasingly moving to implement an A.I. model for claims management.

I am rather partial to a real human making decisions about my health.

This post is not an anti-A.I. screed, but merely a plea for the reasonable deployment of a system that utilizes an existing data base to arrive at a course of action that might have life-and-death implications.

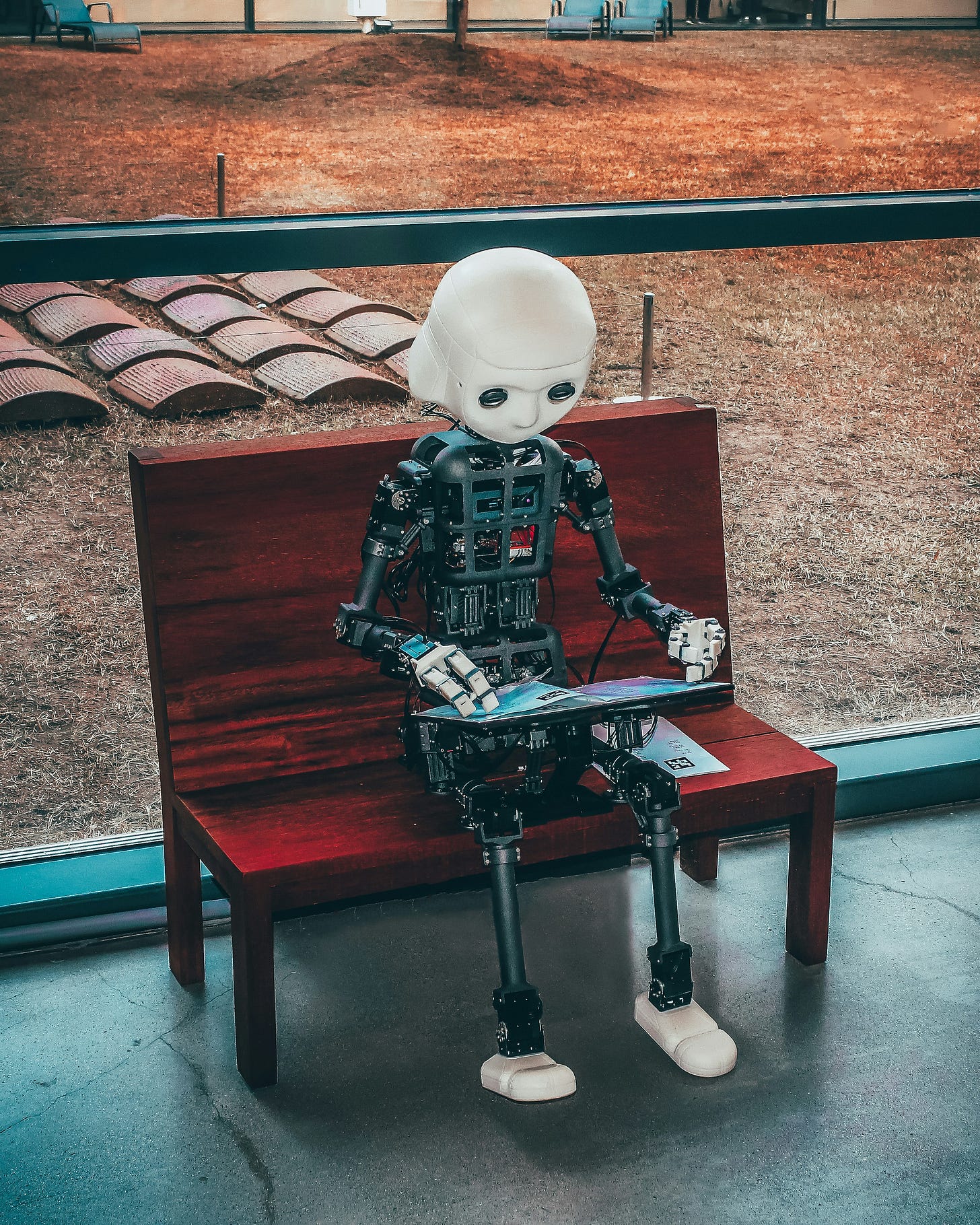

Photo by Andrea De Santis on Unsplash

Stephen Witt has devoted a great deal of thought to the potential—and the dangers—of A.I. He is the author of The Thinking Machine, a history of the A.I. giant Nvidia. He wrote an opinion piece published in the October 10, 2025 issue of New York Times:

I’ve heard many arguments about what A.I. may or may not be able to do, but the data has outpaced the debate, and it shows the following facts clearly: A.I. is highly capable. Its capabilities are accelerating. And the risks those capabilities present are real. Biological life on this planet is, in fact, vulnerable to these systems. On this threat, even OpenAI seems to agree.

In this sense, we have passed the threshold that nuclear fission passed in 1939. The point of disagreement is no longer whether A.I. could wipe us out. It could. Give it a pathogen research lab, the wrong safety guidelines and enough intelligence, and it definitely could. A destructive A.I., like a nuclear bomb, is now a concrete possibility. The question is whether anyone will be reckless enough to build one.

—Stephen Witt

Many of us remember the 1968 Stanley Kubrick film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. The film’s most famous lines are primarily from the confrontation between Dave and HAL 9000: “Open the pod bay doors, HAL,” and HAL’s response, “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that”. Other notable lines include HAL’s calm but menacing, “I know that you and Frank were planning to disconnect me,” and the opening line from the famous song HAL sings while being shut down: “Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do”. (Google A.I. overview). See, it does have appropriate—but limited—applications!

But the very thought that an automated source might override a human judgment is frightening.

During the DOGE debacle earlier this year, there was talk about laying off employees at the IRS and the Social Security Administration and of allowing A.I. to adjudicate matters previously effectuated by human employees.

Witt shares the concern that A.I. run amok could easily pre-empt human hegemony. A worst-case scenario includes the possibility that A.I. could engineer a deadly pathogen and release it into the population.

In the field of academic inquiry, I am used to the the application of a constructed mechanism involving or enabling discovery or problem-solving through methods such as experimentation, evaluation, and trial and error. We refer to this as a “heuristic.” The word can be both a noun and an adjective. Where it is properly applied, one can avoid sloppy or erroneous conclusions. The process is similar to the “peer-review” function of a scientific inquiry.

In the theology field, having an effective heuristic is largely a matter of viewing objective truth through the lens of reason and received wisdom. It is often related to the integrity of a particular theological tradition. One hopes that a genuine and authoritative heuristic will prevent aberrant and cultish devotion, such as one might expect from the Jim Jones colony in Guyana, the Branch Davidians in Waco, or the Heavens Gate cult mass suicide in 1997.

The orthodoxy of mainstream Christian theology is sustained in and by the work of human community, the “lens” through which objective truth is identified and celebrated. The integrity of a particular theological tradition is protected, and the cultish aberrations are precluded.

Similarly, the responsible application of A.I. necessarily involves human judgment as the heuristic by which society is well-served.

A.I. may well prove to be a cost-effective and time-saving innovation—as long as it is controlled by the human mind.

Perhaps some day, Congress can see its way clear to craft effective legislation that mandates sensible restrictions governing the utilization of A.I. But that will require giving the culture wars a rest and actually serving Americans. Machines will not replace us if we are vigilant in maintaining genuine human community.

Because without it, A.I. could kill us all—one application at a time.